Company History As Recollected In 2021 - Part 4

Table of Contents

We’ve officially reached novella length now, although this isn’t fiction. I skipped a lot of details, including minor drama around parting with several partner companies. This second half of my career is more fresh in my mind, but I’m going to keep to the same level of detail.

In part three, we talked about 2013 and 2014, which were “peak Arcen” in terms of success and company output (so far). There was a ton to cover, and despite many setbacks, the company was incredibly successful.

Part four is a story of repeated failure and distress, but I prefer to view it as a story of perseverance in the face of challenging circumstances.

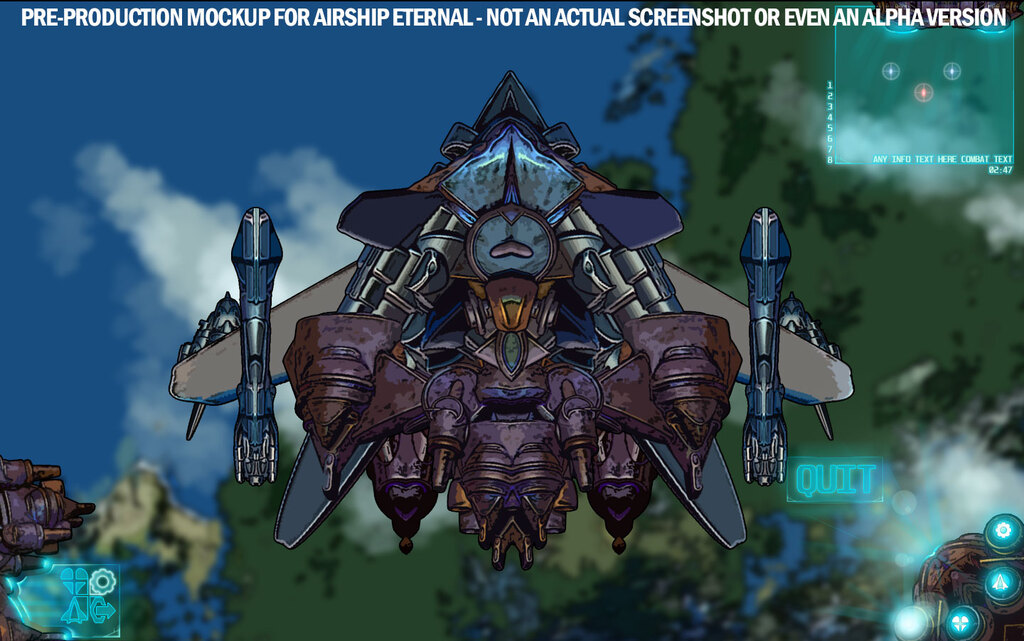

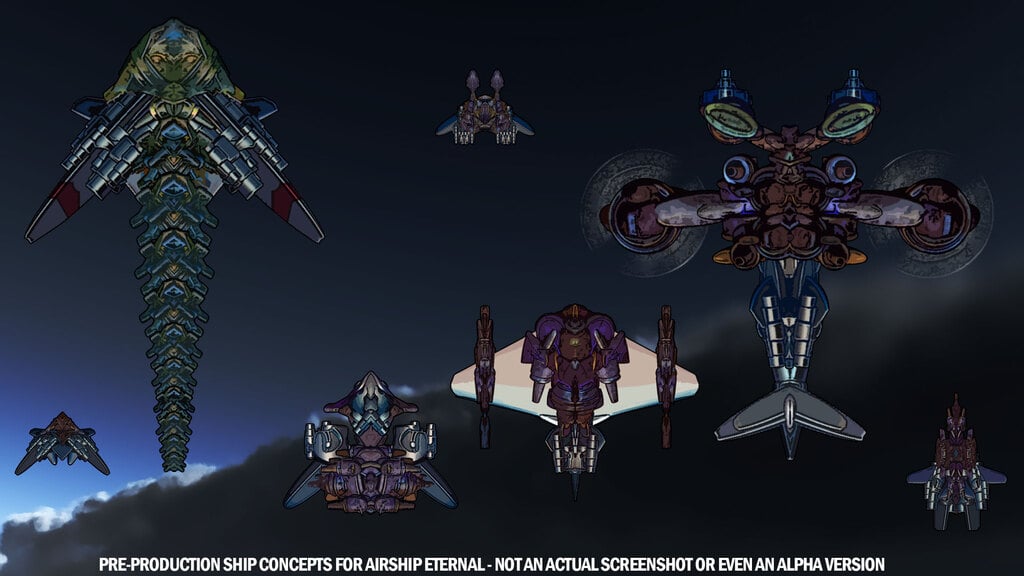

Airship Eternal

I had completely forgotten this was even a game we worked on! Wow, Keith and I had been so excited about it for a while, but it didn’t pan out in prototyping.

Getting Started On… “Spectral Empire”

Ugh. I still have bad feelings when I think about this project, so I’m not going to dwell on it too much. The initial idea was to make a new 4X that was kind of a spiritual successor to Sid Meir’s Alpha Centauri (which I have never actually played or watched, just to be clear). I’m a big fan of the Civilization franchise, though, of which Alpha Centauri was a spinoff. I’m also — as I mentioned in part 3 — a fan of Risk. And of SimCity, Cities: Skylines, and other citybuilders (Pharaoh and Anno are great, etc, although I had never played an Anno game until well after this project imploded).

At any rate, some key parts of this design:

- Having a hex grid (like Civ), but also regions of space under control with various amounts of armies in them (like Risk) is something I wanted.

- I didn’t want to see giant warriors and spaceships and so forth standing around on top of the hexes like you see in Civ. That’s a very board-gamey feel, and can block the view of your buildings. Also, you get into the infamous “stacking of Civ 4 or terrible pathfinding challenges of Civ 5” paradox, which I wanted to avoid.

- I didn’t want “cities” like Civ has, where everything is just line items in a submenu (this is speaking of Civ 5 and back — Civ 6 actually addressed this exact item, though I had no way of knowing they would do that). My idea was to take a lot further than what Civ 6 did, and make each hex either a small building, or part of a larger multi-hex building.

- I wanted to have the various simulated flows of goods and services between buildings in cities or districts, like what SimCity has, but minus the need to put out a ton of roads and set up a bunch of other repetitive bits.

- I wanted the terrain to matter a lot, and have a lot of alien climates.

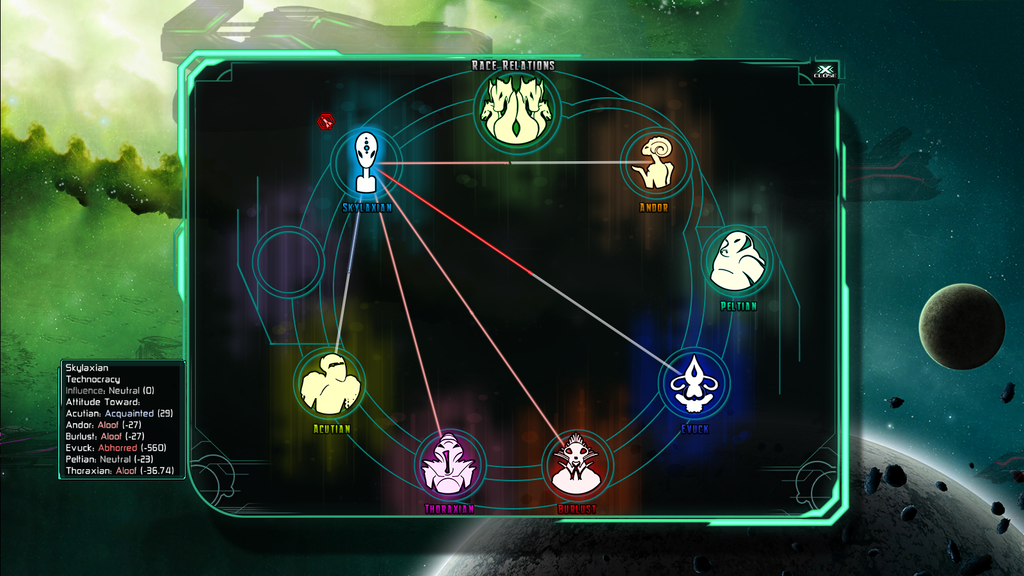

So far, basically all of the items above were something that we were able to achieve, in any number of working prototypes. Building placement was satisfying and interesting. We had all of the races from AI War and The Last Federation, plus three new races, and that was a great starting roster. A lot of the general themes of a simulation game and the push and pull of resources back and forth, and multiple industries and such, were present in abundance in The Last Federation, so none of this was a stretch from things we’d done in the past. The terrain and the citybuilding and all that sort of thing was also stuff that was right in our wheelhouse, and we could do that sort of thing in our sleep.

Overall this project took 18 months, involved 18 people by the time it was over (most of them working fulltime at one point or another), and was never in a fit state for release despite fans being intensely interested in it. For some people, you could tell this was basically the Second Coming in video game form, and our art and music were both great, too.

My job was going to be purely design, which was how Keith and I sorted out our potential conflicts on design ideologies. He was going to be in charge of code design and the technical lead, and so that gave him a very large domain to handle on his own and in his own way, and I could also then just focus on my own ideas and not have to worry about negotiating with actual fans of Alpha Centauri whenever I deviated from that (which was likely to be frequently, since again I have still to ever play or watch that game).

Hiring A Consultant For A New Game Name

The name, though… this was not a good name for a game. Tom Chick had given me such a hard time about Bionic Dues being a name that drove people away, and I still had a pretty vivid memory of Alec Meer writing in PC Gamer that the name “AI War: Fleet Command” was the equivalent of something arriving in a brown paper bag. I was quite proud of A Valley Without Wind when it came to titles, and The Last Federation also had hugely resonated with folks, but clearly my track record was uneven.

I decided that I would just drop Tom Chick himself a line and see if he would consult on the name. I had been on his podcast probably more than any other guest (I think 4 times out of 400), so we were already friends, if distant ones because of professionalism. We worked something out, and the name we ultimately came up with was This World Is Mine. There were some other gems in there, but that was definitely the best.

That wound up not sticking, though, as other people were not as fond of it as Tom and I were, and were not shy about letting me know. I don’t remember where it came from — possibly Keith, he was always good with names — but Stars Beyond Reach became the new title. For a while, it had the subtitle of This World Is Mine, but over time that was dropped. Someday I still want to make a game called that, because it’s a killer name.

Interlude: The “Indiepocalypse”

Work was still progressing apace on Stars Beyond Reach. We had a solid concept, and wishlisting was going through the roof on Steam, and in general we had a queue of excited potential testers that was so long that I was asking them to sort themselves into groups, and then I was taking them in limited batches of 10 at a time because “we can only get a first impression once” from any given person. So… all was certainly well from a hype and engagement standpoint, it seemed.

Even so, it was hard not to notice that overall sales on all of our other titles was starting to slow down. I believe our back catalog revenue dropped by something like half. The following year it was to a third or a half. The year after that, it halved again. Something along those lines. It was severe, and super obviously a departure from any years prior, and it never got better.

This was our experience of the “Indiepocalypse,” which started in 2015 and I’m not sure ever stopped. While some felt like it was a temporary issue and being blown way out of proportion, by 2018 we developers and gamers all were pretty much on the same page that things had changed forever.

I wasn’t very surprised by this, because honestly I had been bracing for this since 2009. If anything, it took way longer to happen than I expected. Let’s look at the market over time:

- In 2008 and prior, you more or less could not be an indie game developer. A lucky few were, through sheer tenacity mixed with luck, but it was not all that lucrative. An even luckier few (World of Goo, Braid, etc) made into the seven figures, but they were somewhat “kingmade” by one platform or another.

- In 2009, many of these companies started making more money, and a few more companies got “kingmade” by various platforms — in the case of Arcen, I’m very well aware that we were kingmade first by Stardock, and then later much more by Valve.

- In 2010 through 2011, it was still a pretty closed system. Those who had been kingmade were able to make a lot of money, and those on the outside were making more money than before, but still frustrated they could not get inside. I had professional acquaintances on the outside who were justifiably furious about being passed by, but what can you do?

- 2012 through 2014 saw platforms opening up more, and more platforms appearing. 9 out of 10 platforms that launched during these years and the years immediately prior would go bankrupt (I must have gotten 15 different bankruptcy notices in the 2010s from platforms and publishers I partnered with). Most — but not all — of my professional colleagues now made it onto the various platforms of their choice (usually Steam), and everyone made more money.

- From 2015 onward, Valve decided to open up their storefront to basically everyone, and did not put any sort of curation system in place to handle it. Their revenue went up a ton, and they spent the following years giving us all graphs showing how not only was their revenue up, but more games by more developers were hitting lots of exciting metrics. They weren’t wrong at all, but everyone noticed the piles of “asset flips” and scams and low-effort junk clogging up the stores. Developers asked for help. Customers asked for help. Customer advocates asked for help.

- Incremental changes happened, and things are better now than they were at various points in the past. I would say that releasing a game in 2018 or 2019 was much better than releasing one in 2015 or 2016, and in 2021 it’s even better. Not like it was in 2013 or 2014 — not even close — but it’s more open and more fair to all, so I can’t complain too much. After all, I was kingmade and on the inside reaping those benefits, so it would be titanic hypocrisy to complain that others were being given a chance. I would have handled it differently, is really all I can say.

- As it stands, the power of any sort of back catalog is pretty much gone, and I can’t even argue that is the worst thing; there are so many games coming out every year that consumers don’t even need to think about playing something from a few years ago. Arguably consumers have more choices of a higher quality now than they ever did under the old closed system. It’s harder for many of us developers, but… so? To some extent, that’s how a market is supposed to work.

As the next few years are discussed, it is important to bear in mind that all of the above is unfolding. I don’t blame anything that happened on the above, but the above didn’t help. Then again, I do think that this added pressure is what pushed me to become a markedly better developer, so we’ll get to that part later, too. I’m not sure if I would have made certain important (correct) choices without all this pressure from the market, but we’ll never know for sure.

"Tales Of Woe" Promo Series

I worked with the same animator who had done The Biscuit Federation to make a new animated series that I wrote and directed and did the audio for. It’s my favorite thing from the Stars Beyond Reach period of time.

Stars Beyond Reach Collapses

Work was still progressing apace on Stars Beyond Reach. In May of 2015 we did one major reimagination of it, trying to make it fun. It didn’t work out well. In October, it was time to do another one, or do something entirely new. After consulting with basically everybody on staff and in my family and friend groups, I decided to do something different.

So what wasn’t working about Stars Beyond Reach?

- It was supposed to be a citybuilder where you compete with other races, but it was really hard to make that engaging enough. Citybuilders are usually inwardly-focused, and 4X games are usually outwardly-focused, and I was trying to do something in between.

- There was supposed to be a big diplomacy element, but that never really even got off the ground. There were many completed designs for it, but we never hit a point where any of them were worth implementing. They’re the sort of thing that sound amazing on paper, but the more designs you see, the more holes you start seeing in designs even before trying them out.

- I really wanted the stories of the cities themselves — you could control multiple at once — to be compelling and interesting and like The Biscuit Federation videos. We modeled this in probably a dozen different ways, ranging from supply chain flows to little “woes” that would happen, to other events that could occur, to a variety of citizen-needs systems. Universally, they were overwhelming. You’d hit “next turn” and a dozen new things would pop up in your face all demanding your attention.

- Placing buildings was satisfying, but building a whole city was not. These things that were fun at first started becoming more tedious as you had more of them, rather than building nicely on themselves.

- Attacking an enemy tile was also satisfying, but waging any sort of ongoing conflict was visually confusing as well as frustrating (no units on the map means you’re losing population or buildings or both — we modeled all of those options, and none were great).

- In general, in summation, the game was trying to be too many things at once. I’m sure that a game could be made in this sort of space, but not really under this sort of pressure.

Arcen was still really wealthy in early 2015, and I wasn’t doing that bad, myself. I tried to never let the company bank account drop below $200k, and freaked out whenever it did. I can recall some months sending out more than $70k in salaries and contracting fees and royalties, though most of the time it averaged more like $40k to $50k.

To put that in perspective, in terms of just how much pressure that was: $200k was at best about 4-6 months of operating buffer. If I spent 2 weeks trying out a new design idea, then this vast machine of people and talent that I had assembled would very nimbly hop on the new idea and make it a reality, but each week of that was burning something like $10k into ether.

I’m actually really proud of the fact that I was still able to experiment and strive for greatness in the design under those circumstances, but in this particular case, “great was the enemy of good.” For this game to break even or make a profit, and to keep this giant machinery of people fed, I felt like this game had to be monumental. I was missing the key perspective that really, any competent, heartfelt entry in this genre probably would have been viewed as such. I didn’t need to have the translation of alien languages as a feature, or blend in personal stories of individual citizens. The broader empire-wide scope would have been fine, with some adjusting, probably. But I wanted more procedural storytelling masterpieces, on top of all the rest, and that more than anything else probably sank this project.

Truthfully? This whole section is the thing I am least certain about in this entire novella of a company history. I remember what it was like to spend so much money, and the anxiety that caused me. I have the spreadsheets showing how much was lost. I remember all the people, and I remember how it felt like a limb had been amputated when they were gone. I don’t remember details of each build, or each failed design. Pretty much all of that is semi-public, and an Internet archaeologist could comb through it. I personally… don’t have a desire to do so. Here’s the most direct record of links and such.

At the core: I remember that everyone working for me did their job, really well; and that nothing I tried, myself, fully turned out to anyone’s satisfaction. There was a lot of faith in me, such huge confidence that I’d figure it out. I even enlisted my dad for lengthy discussions and whiteboarding. I probably wrote 300,000 words of designs and content. It was the first time that I just really… couldn’t make it happen. It cost a lot of people their jobs, and cost me a lot of money.

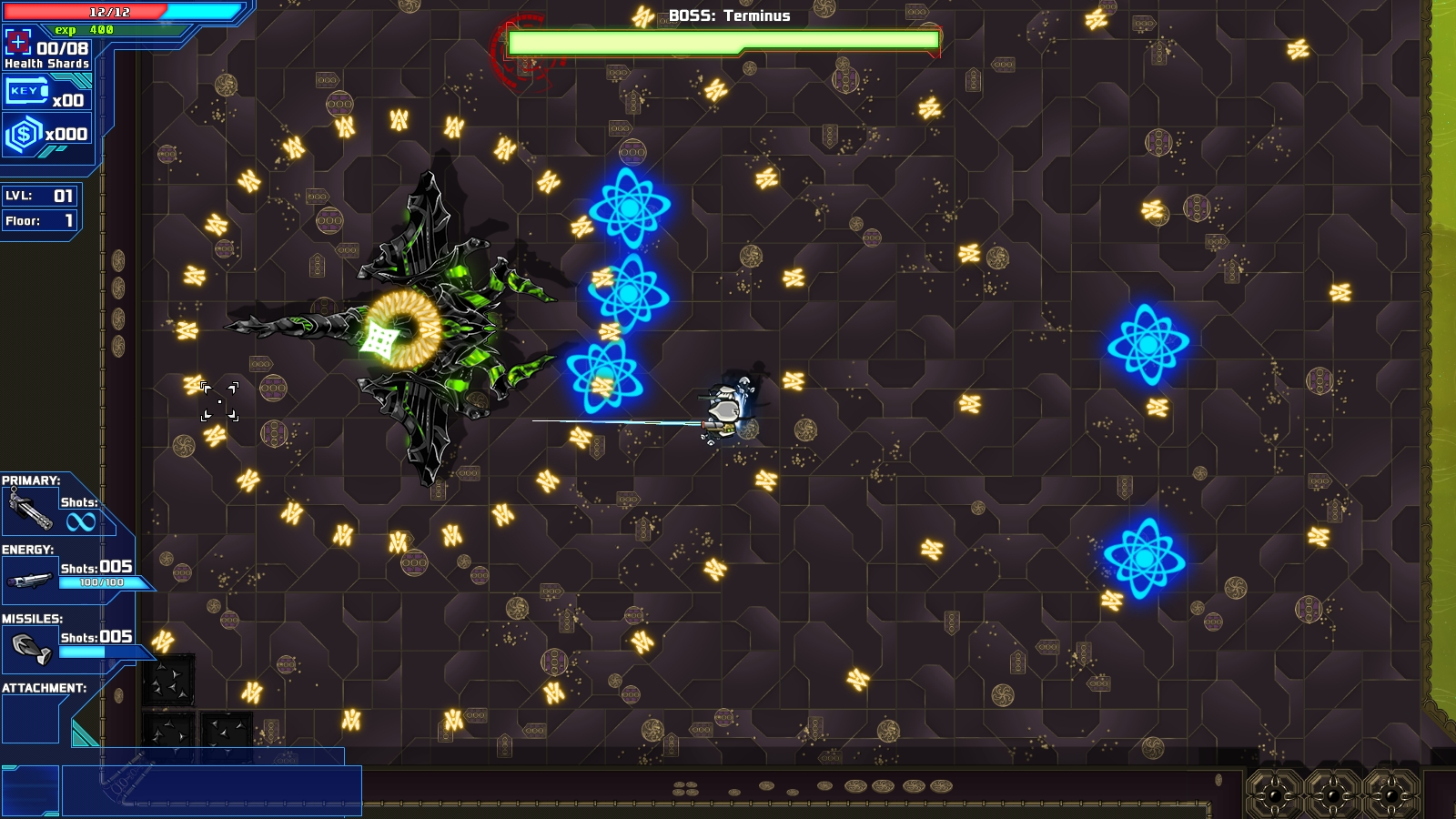

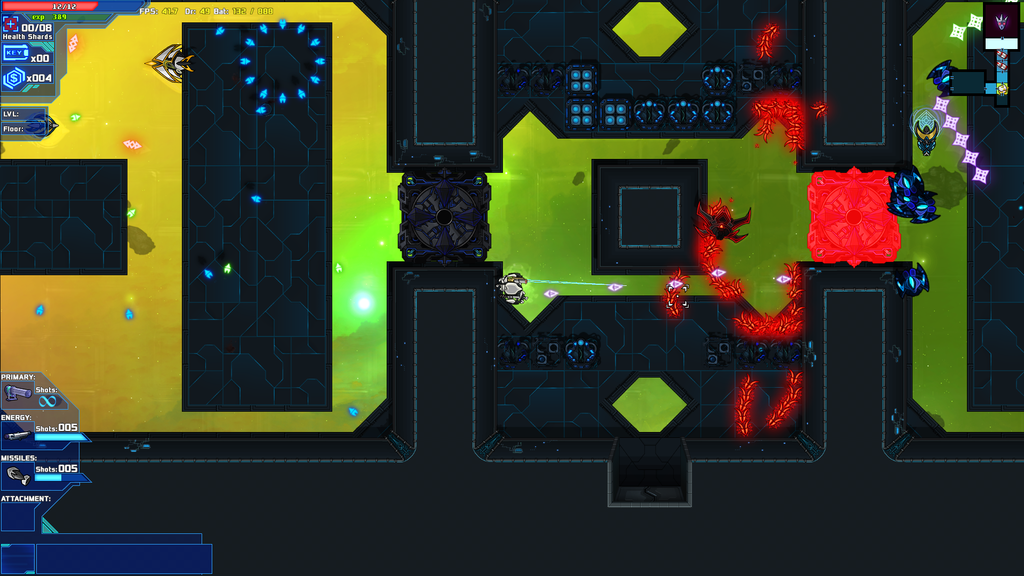

Trying Something New: Starward Rogue

October 2015. A lot of staff lost their jobs, as I mentioned, but the core team remained. Plus a couple of other new specialists. Remember how The Last Federation had been a bullet hell SHMUP for a while? I sure did. It was super fun. And we had Misery in our pocket, who was such a master of that sort of design.

Many of us on staff were huge fans of The Binding of Isaac (and others of us, it should be noted, found it juvenile and deeply offensive on several levels). I was in the former camp, being a huge fan, though I did also find it juvenile and crass. BOI is essentially a procedurally-generated version of the original Legend of Zelda dungeons, with a whole different item and progression structure, if you really think about it at its bones.

We very quickly set out to make our own game in that vein, minus any of the crassness and with a whole lot more bullets on screen. Nuclear Throne was imminently going to be out, and I think Enter the Gungeon was also either recently out or soon to be out. So this subgenre had major attention, and lots of people were interested in it. Competition was clearly tough in every genre, though, so what else can you do?

We decided that we would make this game in a span of about three months, with a staff of something like… I think eight of us? This time, I was working on design and programming, and was in charge of the level editor and the procedural generation, among other things. Keith was in charge of the upgrade systems and the way that buffs and character and monster interactions worked, among many other complicated bits. Cath was on environment art, Blue was on enemy and item and character art, Misery was on boss design, and there were a bunch of us on enemy design and room design. I was by far the least-expert of those discussing those elements, but I did get to contribute, which was fun. I was most-expert on plenty of things.

We got to work, and it was immediately clear that this was a fun title, and it looked like it was going to be one of our most polished titles to date, too. Funny how that works. But in the meantime…

The Lost Technologies

The main team was all working on Starward Rogue. There was no time for any of our main staff to spare from that giant job for anything else. That said, the temporary cessation of work on Stars Beyond Reach had certainly been noted, with dismay, in our fanbase and to a lesser extent outside of it. But we were on a rush schedule, holy cow things were tight, and I didn’t have time to pay attention to that.

Draco18s has been a longtime member of Arcen’s fanbase, and is an excellent programmer as well as having given many insightful bug reports and feature requests and constructive criticism over the years. He and I had been talking about collaborating on something from as early as April of 2015, and in September of that year, personal circumstances on his end led to me suggesting that we finally actually do the collaboration, in the form of a very-hands-off-for-Arcen DLC for The Last Federation.

At the time we were talking, I thought the current design of Stars Beyond Reach would still turn out peachy (well, I hoped), but this was clearly going to be mutually beneficial. Sales for TLF were slowing down, but not any faster than AI War’s finally were, or any other game in our back catalog was. This would be a chance to boost that franchise with very low risk, and also provide income and experience for Draco in a transitional time in his own life.

A new DLC for it couldn’t involve our artists much, because they were super busy, and it couldn’t involve any of the other programmers or designers because we were equally busy. This was the first (but not last) time I was ever going to partner with someone I trusted to make something pretty much completely without me, and without much in the way of my resources, even; I think there was maybe a music track or two added for this DLC, but mainly what I was providing him was my intellectual property and audience.

I had discussions with multiple people about DLCs for Bionic Dues that would have followed a similar pattern, but ultimately none of those ever took off. I wasn’t actively looking for anyone, but people tended to approach me for things (still do), and saying yes more than I say no is how I wound up getting so many bankruptcy notices from distribution partners and publishers. I regret nothing — and actually, I get pitched like five times a week and just ignore the vast majority, so I guess I really do say no way more than yes. Most are some sort of template email, so I don’t feel the need to respond to something that is being blasted to a bunch of companies at once.

The Lost Technologies released quietly in mid-November 2015, which was… in retrospect a pretty bad time of the year. That said, it did decently — it earned well enough for Draco that it was well worth the time he put into it, and the same was true for Arcen. Beyond that, it did not really revive the franchise or cause any sort of major stir. Indiepocalypse, right? But this was also a small addition to a niche game, so I wasn’t super surprised either way.

Looking back, I am actually surprised at some of the super-cool features I forgot about, like the ring worlds, the technocracy, and some of the other new weapons and such. This is bigger than I remembered!

Chronologically, this little DLC was the last product that Arcen has ever released (as of October 2021) that has broken even on investment, let alone made a profit, so I think it deserves a special mention for that if nothing else.

Starward Rogue Flies Into The Sun

Starward Rogue is a fantastically good game. I feel a bit extra free to say this because of how many people other than me made the really important parts come to life. I was the producer and project manager, and so steered things. But there was no central lead designer in a traditional sense. Rather, there were multiple lead designers, all focused on different areas of the game, and all coordinating really well with one another and with all of the content designers, artists, programmers, and so on.

There are a lot of ways you can structure a company, let alone a project. When it comes to the company itself, I am the sole owner and anyone who works for me is working for me. That’s fairly simple.

That said, on each project over the years, I have adopted various degrees of partnership (in the sense of intellectually/practically, as well as in the sense of profit sharing).

- Skyward Collapse was kind of like a lead researcher with a team of researchers helping out, to try for an analogy.

- Tidalis was like two bands touring together and the larger band showcasing the smaller one’s act as a central part of their own work.

- The Lost Technologies was a simple work for hire in the classic sense.

- Stars Beyond Reach was run with a hierarchical structure identical to that which you would find in a AAA studio, just smaller in scale.

- Cretaceous and other projects that didn’t end up coming to life were kind of like informal jam sessions amongst friends in a band, trying to come up with some new music. A lot of our projects started this way, The Last Federation included, and then shifted to some version of the hierarchical structure.

- Shattered Haven, and in general AI War prior to 2010, were solo projects where the person calls in some expert help to work on sub-parts of a mostly-complete job.

Starward Rogue was different. The best analogy I can think of is going to make you cringe, but so it goes: this was like a group project in school. This was far more collaborative, far less hierarchical. We had a tight schedule, and our expertise was fairly evenly spread amongst everyone. Out of the people working on this game, there is no group of 75% of them that you could form that could have finished it properly without that last 25%.

This sort of flat structure is what Valve tends to tout for their own company, and they tend to credit some of their largest successes to it. That said, they do have more redundancy in their staff (this is a good thing, and comes from being a larger company), so it’s not quite the same. But professionally, it’s the closest thing I can think of.

Ooh! A very small orchestra is actually another good example. Yeah, you might have two violinists, but you need them both. And neither of them can go pick up the bass, and the percussion section and composer and brass and woodwinds all have their own deals going on. A larger orchestra has (again, good) redundancy by having more members of each instrument, but if you’re talking about a small orchestra just coming together for a few performances, you can do without the redundancy. It means that everyone has to trust everyone else, and that everyone needs to really be on the ball and truly know their stuff. It means everyone needs to focus. And when that happens? Man, what a performance.

I haven’t ever seen anything like that before in my career, and I doubt I ever will again. I was really humbled. And then almost everyone got laid off.

A Brief Look Back From The Perspective Of Early 2016

This post, which I linked to right at the end of the above section, goes into a lot of detail, some of which conveniently slips my mind. A few key points:

I worked all of 2012 for free (later I worked 2016 and 2017 for free).

This point in early 2016 was a bit higher in company debt than I remembered. I had put up massive amounts of my personal money and all of the company money, plus taking on debt, to avoid laying people off.

Not only did this not work, not even a little bit, but it left me even more stressed-out and in a tough financial spot that I’m still not quite out of (though things are improving, kinda-sorta).

From a realistic perspective, if you look at money out of the company versus money in, I worked 2015 for free also. Yes I was paid a salary in 2015, and it was a pretty generous one, but I also invested back in more than double that.

I still don’t quite know what to do with this information. I have many complicated feelings about it. My marriage was already having trouble for personal reasons (nothing exciting or dramatic, it’s just personal), and all of this was not helping matters. She and I had been together for 15 years at this point, from when we were high school students with no money, all through university for both of us, and to quite a lot of wealth… which came with extreme ups and downs, given this industry and market. I’m not really going to comment in any more depth on that aspect of the topic, except to note that I had responsibilities as a father and a husband, as well as a seller-of-products, an employer, and various other roles. I think a lot of these things got away from me for a while there.

Let’s Take A Moment To Think About Guilt

My entire professional career as a game developer has been complicated and clouded by a profound sense of guilt. You may be able to guess why, but it took me a long time to figure out.

For context:

I worked for eight years in tech prior to that, and never had any problems, despite going from data entry intern to CTO. I could always tell that I was being promoted based on my merits, and what I had tangibly created and could do that nobody else in that particular company could do at that time. There were layoffs and occasional drama, but I never felt any sense of personal guilt at any time.

I felt many emotions, but the situation was not of my making, and my contributions tended to make things better, not worse.

So why was my relationship to Arcen different?

Well… I got kingmade by Valve. Yes, AI War: Fleet Command had a lot of merit. Yes, I worked my butt off with the press, other distributors, and players themselves in 2009 to help it spread in a grassroots fashion. The amount of time that I spent popping into random forums and talking to people and helping them understand the game or fixing gripes they had with it really can’t be understated. I treated this whole thing like I was running for some sort of office or something.

Even so, in the end Valve only said yes — despite all my work — because two high-powered people had a conversation, and one of them recommended four games, AI War among them. There were maybe a dozen other games that I would have considered equally worthy, but they were not mentioned and so they were locked out of the main lucrative marketplace for another three or four years.

And once I was in… I was in. I didn’t have to do the grassroots thing anymore. I could fire off an email to Rock Paper Shotgun or Kotaku and head back from their chief editor. I could get onto the Gamespot podcast and spend an hour talking about what the new hardware capabilities of the PS4 and the XBox 360 would mean to developers in practical terms.

Most importantly, I could think up a new game, and once I was satisfied it was good enough for my purposes, I could take it to Valve and they would say yes. Just like that. I was always terrified that they would say no, but they never did. Even after Tidalis and Shattered Haven flopped, I was still in their good graces. This gave me an insane amount of freedom to experiment and do all sorts of things, and that in turn fed the cycle of the press saying “Arcen stuff isn’t always the very best, but it’s always fascinating.”

If Valve had told me no after AI War, I think I would have had an easier time emotionally. I would have had to work for future games to get in there like any other developer. But I didn’t have to work on that sort of thing. I got to experiment, and I got to fail in relative safety, and get up and try again. All the while wondering if I really knew what I was doing at all, and having certain voices on the internet very loudly opining that I most definitely did not.

I thought about acting as a publisher for other indie games, but I knew that would be pushing my luck. If Arcen as a developer had free reign to put out games on Steam (which was never entirely certain), Arcen as a publisher trying to bring in friends and strangers under its coat was really not a good idea. I was quite aware of the fact that I was kingmade, but also that I served at Valve’s inscrutable pleasure. They made up 80% of my revenue, and if I pissed them off, my business was gone for good. They make up even more of my revenue now, but since the market is wide open now, we no longer have that kind of relationship.

To be clear: no one at Valve ever said anything cross to me, or intimated anything. I was never threatened or coerced, and in fact I was never treated with anything but kindness and indulgence. At the same time, they largely ignored any developer they didn’t want to work with (same as I ignore potential contractors and partners I don’t want to work with), and I am intelligent enough to know that their interests and mine would not always align.

So when your entire career feels like maybe it was possibly un-earned to some extent, and at the same time it can be taken at any time by someone else’s whim, how do you cope with that?

For me, I coped by providing careers — dream jobs — to other people, and providing them a sense of security that I lacked. I generally picked people who were incredibly talented but NOT already majorly successful, and then I paid them above market rate. I didn’t ask for overtime. I made it clear that whatever happened, we’d figure it out together. We were a team, and I had their backs. If I was working for free for a year, this was not information I shared with them.

I was pretty free with the general inflow-outflow stats of money, and made the stakes clear when there were stakes (because we’re talking about adults, not children), but I developed a pretty solid habit of “pulling rabbits out of hats,” which caused a lot of arguably-unjustified faith in me from some of the staff and contractors. And when giant windfalls came, which they invariably did prior to 2015, then everything was always okay again for a while. I remember one time, I think it was in 2011, we made $130k in 24 hours with one of the sales Valve was running in the summer. This was just a random summer sale, but suddenly in the middle of one summer day we were averaging several thousand dollars a minute in income.

This sort of thing messes with your head. For me, it made it almost impossible to lay people off. If there was any chance, I just couldn’t do it; I had to exhaust every avenue first. Stars Beyond Reach was clearly a troubled project from early in 2014, and I should have just dropped that and worked on something else. But there was hype among fans, the press was already talking about it, and most importantly… what was I going to do? Just rip the rug from under all these people because it seemed like there might be trouble in the future?

I couldn’t do that. In 2021, knowing what I know now from the second half of my-career-so-far, I’m not planning on ever hiring staff again if I can avoid it. I love working with people, but it will be on a contract basis for a limited scope of time and work. Open-ended contracts where I start feeling responsible for others and their entire families is not a healthy thing for me, apparently.

Time To Learn 3D Programming And Design

I had hit a wall in 2D space. I have an ever-growing list of game design ideas, but already several of them had been foiled by the simple fact that I could not represent them attractively in 2D (Airship Eternal, Starport 28, and Cretaceous among them). There are a lot of things that work in pixel-art in 2D, because you can fake perspective in various ways, but then any higher fidelity and it stops working without moving to 3D.

Additionally, even with games that had been released, like Bionic Dues, one reason that the graphics suffered was from being 2D. To properly let the player understand what is going on, you have to somehow differentiate depth. This is easier to do from an isometric point of view, but from top-down or side view it’s very very hard. In Terraria, you only learn which plants you can walk past, and which block you, by experimentation; there is nothing overly visually different about them. There are a hundred problems like this that are solved by 3D.

I had been programming “2D in 3D” since 2002, but all of the vertex math, and matrix math, and vectors, and transforms had always made my head spin. Vertex normals are a strange sort of lighting magic, and none of the shader languages are fully documented anywhere that I can see. You couldn’t just go buy “HLSL In A Nutshell” and then devour the language specification. So I had always been really wary of trying to make this jump, and felt like it was beyond my understanding.

In 2016, after Starward Rogue collapsed, I made the jump to this in earnest. Within about three months, I was fairly competent at it. Go figure. Compared to now, five years on, I was still very new, but I could do the work.

Keith LaMothe, Daniette “Blue” Shinkle, and myself were the only three remaining people working at Arcen, but “Cinth” also was helping out in this new phase of things. Keith returned to work on Stars Beyond Reach and see if he could salvage that project where I could not (spoiler: no), and so it was just Blue and Cinth and I on the next project, which would be in 3D.

In Case Of Emergency, Release Raptor

Have I mentioned I really love dinosaurs? Because I am just enamored with them. One of my favorite games was the early-90s Sega Genesis version of Jurassic Park. You could play as the raptor.

I wanted to do the same thing, but in 3D and with procedurally-generated levels. Jurassic Park had been an action platformer, and I wanted to make an action dungeon crawler. I wanted to have things like dismemberment of enemies, but at the same time make this kid-friendly, so the enemies needed to be robots.

Three months in, I was ready to show off the first preview of the game, which included lots of technical details and other updates. Later that month, I talked about how yes, I know it’s not really a velociraptor — it’s an achillobator. I do in fact take my dinosaurs seriously, even when they are doing silly things like fighting robots.

If the details of development on this interest you, I documented them in detail. They became increasingly self-deprecating, and the release kept getting pushed back more and more. In July I explained what the game was going to be, and why I was running so behind. I was building a 3D level editor (useful), and overly concerned with things like the raptor clipping through objects (not useful, and an unrealistically-high standard for even a AAA game). Then again, I was also learning about lighting in a lot of depth, putting together a whole new toolchain, getting into the details of advanced 3D graphics programming, and on and on and on and on. I’m really struck by how much I love the visuals in that game.

On August 24th, the game was released into Early Access.

On August 26th, the game was pulled from Early Access (by me), all customers were refunded, and what existed of the game was made freely available for anyone to play.

The short explanation: people were wildly misunderstanding what the game was, thinking it was a joke physics game like Goat Simulator. And I had spent so much time on the graphics, the toolchain, the feel of the raptor, the level editor, the procedural generation in 3D, and so on… that the actual core gameplay was way too unfinished for anyone to really get an idea of what it would be like in the end. Also, the game was selling stupidly poorly.

I still get people who tell me things like “I really like all of your games, except for that… raptor thing, whatever that was about.” The narrative had essentially become that I was trying to cash in on Goat Simulator somehow, and that this was a very un-Arcen game, made in a rush and without our usual care.

I resolved to use Early Access differently from then on, though I still remembered how much people had misunderstood Shattered Haven even when it was a complete product on launch (seriously, what part of that is turn-based tactics?). Clearly I needed to get better at messaging, particularly in the new market where there’s so much more competition for attention and time.

As far as Release Raptor being a rush job, it had twice the calendar months of development time of Starward Rogue, though that game had a much larger team on it. Raptor also had roughly 120% of the development time that Skyward Collapse did, and that had been quite popular for a time.

Once again, I found myself with a lot of new information that I didn’t really know how to process. The core lesson was that public perception could be wildly different from reality, and that once a narrative takes hold, there’s no real shaking it. This above any other reason is why I pulled the game as quickly as I did.

Up Next: AI War 2, Silent Halls, and Kickstarter

I thought I’d be able to finish this up in four parts, clearly not! I think it’s fairly obvious that it’s therapeutic for me to be laying out all my thoughts like this, but hopefully it’s also useful to someone else either just out of curiosity, or if they’re thinking about starting an indie development studio.

I get asked a lot more about the things that didn’t work than I do about the things that did, and the raptor game in particular still seems to baffle people, so there you go. I also think that sometimes folks have been confused or frustrated with how I made decisions during the rough years, and so looking at the collapse of Stars Beyond Reach in depth, as well as the underpinning of guilt that pervaded most of my career, helps put that in perspective.